HOW AND WHAT

One of the problems about trying to open up photographs, to get a grasp on how they work (at least at the level of meaning) was for a long time hampered by the concepts brought to them from literature of ‘form’ and ‘content’ which seemed from the start to fragment and divide the object which in our initial encounter we had experienced as a unity. Content was embodied in form, depended on it but was also understood as separate from it, it was what the object (photo) meant. Rather like liquid in a vessel, it could be designated as separable from its specific presentation and transferrable; in that respect form was accepted as a necessary but lightweight adjunct to the main business of visual communication, the content. Even in the late 1970s one can see Sontag battling with the same issues which as semiotics, and Barthes and Metz’s writings became more extensive and better circulated get displaced. Using the latter it is possible to offer an analysis which begin to show that what something means is at least as dependent on the “how” of what it means as much as what is shown. Using the latter it became possible to think around photographs not just in terms of what they show but how they show what they show and the part that plays in what the photographs means.

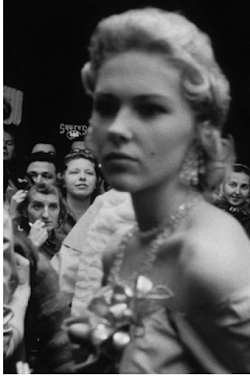

|

| Hollywood Movie Premier 1958 |

For example, to make this more concrete, using ideas from Barthes and Metz we can approach Robert Frank’s image Hollywood Movie Premier 1958, (Frank 1958). This black and white photograph has centrally placed and occupying about two thirds of the picture plane an image of a glamorous blond starlet, head and shoulders. Not just the caption but her clothes, hair style, jewellery, etc suggest that it is the 1950s and America or do so if one already has certain knowledge that allows that detail of recognition. Behind her at a distance, between her shoulders and the photo’s edges, at the opposite side of the (unseen) red carpet to the photographer are a line of women, in appearance much less glamorous or expensively dressed. The initially odd thing about the photograph given the then rules of good composition and clear subject matter is that the centrally placed woman who occupies most of the picture, and therefore one expects to be the subject, is (slightly) out of focus, the women beyond are sharply in. In effect, one wants to say, this is a photograph about fandom not about the movie starlet and that it is so is because of the ‘how’ of its imaging. Metz writes about what he designates as ‘specific’ and ‘non-specific’ codes that combine in an image: the former being those elements that contribute to the meaning of the image that are specific to the medium, e.g. in the case of photography, framing, depth of field, tonal values, angle of shot, etc, the latter codes that are at work in and that we have learnt from more general social experience, e.g. facial expressions, body postures, hair styles, clothes/fashion, interior design, architectural features, etc. The Frank photograph draws upon and puts all these codes into play but what makes it have the particular meaning that is being claimed here, as opposed to other possible photographs that could have been taken at the same moment from the same spot is its focus and depth of field. The same event (what Barthes calls the ‘pro-photo’ event, the event/scene before the camera (Barthes [1961] 1977) could have been shot using the same depth of field but with the actress in focus and the spectators out in which case it would have become a more orthodox image of her with blurred background, it could also have been shot with a greater depth of field in which case both she and the spectators would have been in focus. The point being that in each of these alternatives the event before the camera would have been the same, what gives the actual photograph its particular meaning as being a study of fandom is how it was photographed: how it is what is it is makes it what it is. An image is always a combination of a pro-photo event and its manner of recording, though common sense tells us otherwise (and many forms of photography, e.g. advertising, fashion, pornography play on that), the pro-photo event is not in itself retrievable from the image. Metz’s writing at this point focused on ‘signifiers’ internal to the ‘text’/image, rather than as is discussed later, how one’s reading a signifier or even recognising a signifier as such is dependent upon knowledge that one brings to the ‘text’ and the context of one’s encounter.

What is exemplified here is that the work drawn off of semiotics in relation to the visual demonstrates that engaging with images is active, involves an act of reading or decoding. This it is suggested is true of all images not especially art images, that in reading all images certain knowledges and competences are drawn on. What marks the difference on this account between high and ‘low’, ‘mass’, ’popular’ culture is not that one is engaged with actively and the other passively but the different knowledges that are drawn on in those engagements. The binaries art/mass culture, active/passive consumption become uncoupled.

Refs:

i) Frank Robert, 1959, The Americans. Grove Press. New York: 140

ii) Metz C, 1973 “ Methodological Propositions for the Analysis of Films” Screen (Spring/Summer):89-101.

iii) Barthes R, (1961) 1977. “The Photographic Message” in Image-Music-Text trans Heath S. Fontana. London.